Investment by women, and in them, is growing (Economist)

Much of the wealth transferred in the coming decades will end up in female hands

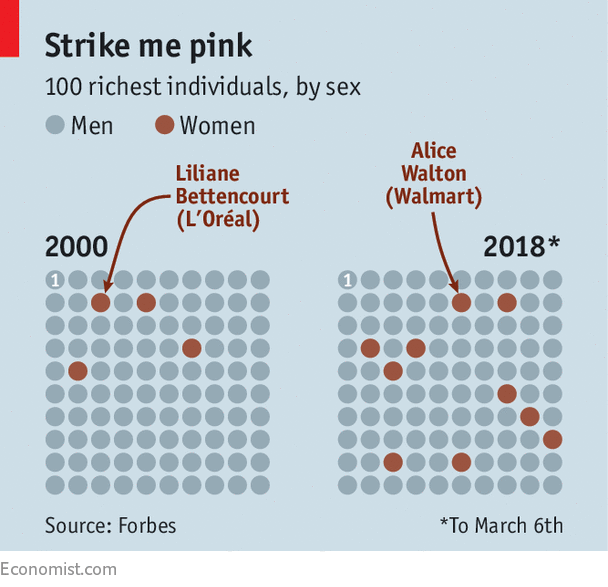

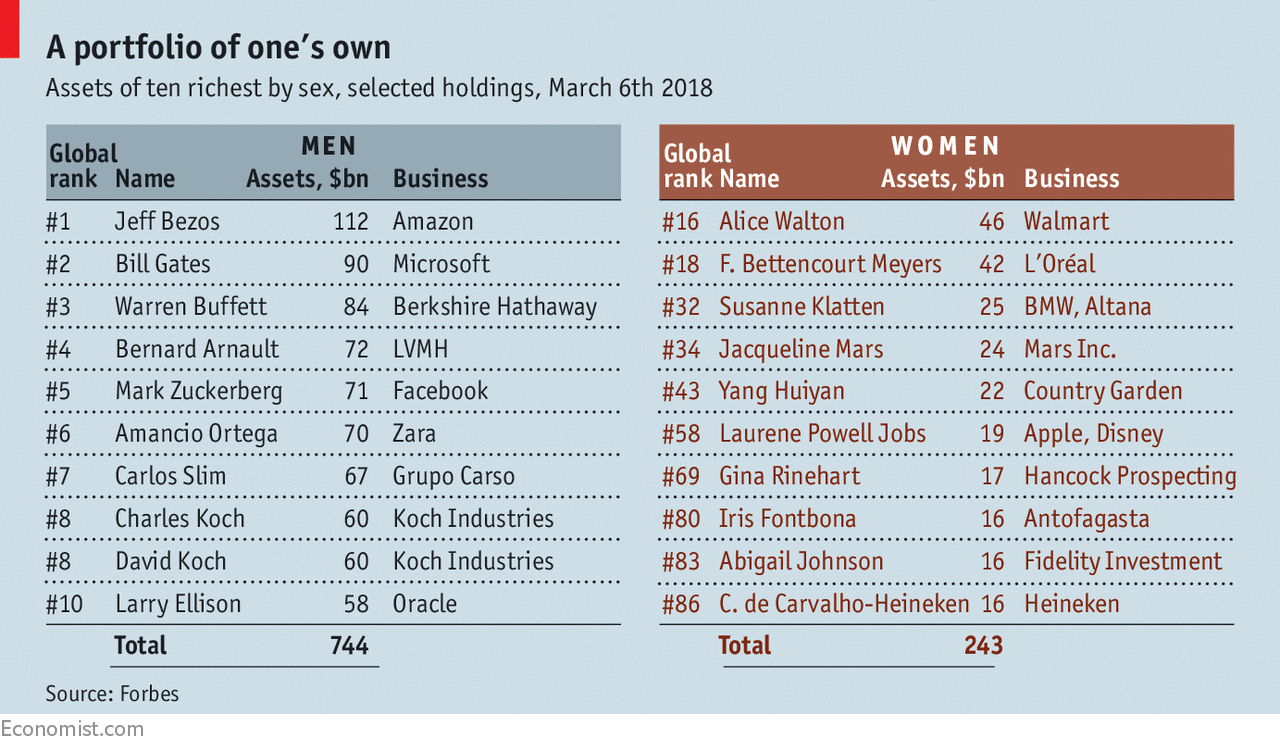

MARCH 8th, International Women’s Day, always brings a flood of reports about gender inequalities in everything from health outcomes to pay and promotion. But one gap is gradually narrowing: that in wealth. As money managers seek to attract and serve rich women, and as those women express their values through their portfolios, the impact will be felt within the investment industry and beyond.

According to the Boston Consulting Group, between 2010 and 2015 private wealth held by women grew from $34trn to $51trn. Women’s wealth also rose as a share of all private wealth, though less spectacularly, from 28% to 30%. By 2020 they are expected to hold $72trn, 32% of the total. And most of the private wealth that changes hands in the coming decades is likely to go to women.

One reason for women’s growing wealth is that far more of them are in well-paid work than before. In America, women’s rate of participation in the labour market rose from 34% in 1950 to 57% in 2016. Another is that women are inheriting wealth from husbands, who tend to be older and to have shorter lives, or from parents, who are more likely than previous generations to treat sons and daughters equally. As baby-boomers reach their sunset years, this transfer will speed up.

All this will have big implications for asset managers. Take risk-profiling. Surveys show that men’s attitudes to risk are typically more gung-ho, whereas women are more likely to buy and hold, which leads advisers to conclude that men are less risk-averse. And men are more likely to say that they understand financial concepts, which might seem to suggest that they are more financially literate.

But it may be more accurate to say that women are more risk-aware and less deluded about their financial competence. A study in 2001 by Brad Barber and Terrance Odean, academics in the field of behavioural finance, showed that women outperformed men in the market by one percentage point a year. The main reason, they argued, was that men were much more likely to be overconfident than women, and hence to carry out unprofitable trades.

Another difference is that men are more likely to say that outperforming the market is their top investment goal, whereas women tend to mention specific financial goals, such as buying a house or retiring at 60. Affluent women are more likely to seek financial advice and fewer direct their own investments compared with men, according to Cerulli, a research firm. But they seem to be less satisfied with the advice they are getting. A survey in 2016 by Econsult Solutions, a consultancy, found that 62% of women with significant assets under management would consider ditching their manager, compared with 44% of men. Anecdotally, millennial women who inherit wealth are prone to firing the advisers who came with it.

A few investment firms focusing on wealthy women are springing up, such as Ellevest (motto: “Invest Like a Woman”). Other money managers are seeking to hire female advisers and setting up dedicated teams for female clients. Some have taken the daring step of making women more prominent in their marketing material.

“It’s critical for our business that we recognise the trend of rising women’s wealth and respond appropriately,” says Natasha Pope of Goldman Sachs. That response goes well beyond better communication with women. It means recognising that women, particularly younger ones, are more likely to look for advisers who can help them invest in a way that is consistent with their values.

In a recent survey by Morgan Stanley 84% of women said they were interested in “sustainable” investing, that is, targeting not just financial returns but social or environmental goals. The figure for men was 67%. Matthew Patsky of Trillium Asset Management, a sustainable-investment firm, estimates that two-thirds of the firm’s direct clients who are investing as individuals are women. Among the couples who are joint clients, investing sustainably has typically been the wife’s idea. Julia Balandina Jaquier, an impact-investment adviser in Zurich, says that though women who inherit wealth are often less confident than men about how to invest it, when it comes to investing with a social impact “women are more often prepared to be the risk-takers and trailblazers.”

The newest trend within values-driven investing is to use a “gender lens” to make investment decisions. Just as environmentally minded investors may ask about their portfolio’s carbon footprint, or seek to invest in green-energy projects, so too a small but growing group of investors want to know what good or harm their money is doing to women.

According to Veris Wealth Partners and Catalyst At Large, investment-advice firms, by last June $910m was invested with a gender-lens mandate across 22 publicly traded products, up from $100m and eight products in 2014. Private markets are hard to track, but according to Project Sage, which scans private-equity, venture and debt funds, $1.3bn had been raised by mid-2017 for investing with a gender lens.

As with green investing, a gender lens comes in different strengths. Mild versions include mainstream funds and exchange-traded funds (ETFs), such as the SHE-ETF by State Street, that filter out listed companies with few women in senior management. Super-strength versions include funds that invest in projects benefiting poor women in developing countries. These may make it clear that they offer higher financial risk or lower returns, which investors may accept as a trade-off for the good that they do.

In any investment strategy led by a single issue there is the risk of overexposure to certain industries or companies. Lisa Willems of AlphaMundi, an impact-fund manager, says she tells clients who ask for a “gender fund”—as an endowment did recently—that gender “is a lens, not a bucket”. In other words, it should not be regarded as an asset class in itself.

But there is no evidence that employing a mild gender-lens need mean forgoing returns. “It’s the integration of gender into investment analysis,” says Jackie VanderBrug of Bank of America, a co-author of “Gender Lens Investing”. That may even lead to better financial performance.

Several studies have shown that companies with women in senior positions perform better than those without. Although this is correlation, not causation, to an investor that distinction should not matter. If diversity in an executive team is a proxy for good management across the company, a gender lens could be a useful way to reduce risk. If a business is tackling gender-related management issues, says Amy Clarke of Tribe Impact Capital, the chances are that it is dealing well with other risks and opportunities.

Since the early 2000s RobecoSAM, a sustainable-investment specialist that assesses thousands of public companies on environmental and social criteria, has included measures of gender equality, such as equitable pay and talent management. After realising that in the decade to 2014 firms that scored well on these measures had better returns than those scoring poorly, it launched a gender-equality fund in 2015. Since then it has outperformed the global large-cap benchmark.

The share of companies reporting the gender make-up of senior management to RobecoSAM rose from 35% in 2012 to 54% in 2016. And the number reporting gender pay gaps rose from 21% to 31%. But gender-lens investing is still constrained by a paucity of data.

Anyone who wishes to invest in firms that benefit women who are not employees will quickly find that there is as yet no systematic way to measure broader “gender impact”. Even inside firms, data are lacking. “We need to move beyond just counting women and start taking into account culture,” says Barbara Krumsiek of Arabesque, an asset manager that uses data on “ESG”: environmental, social and governance issues. It is urging firms to provide more gender-related data, such as on attrition rates and pay gaps. Just as its “S-Ray” algorithm meant it dropped Volkswagen because the carmaker scored poorly on corporate governance well before its value was hit by the revelation that it was cheating on emissions tests, in future it hopes information about problems such as sexual harassment could help it spot firms with a “toxic” management culture before a scandal hits the share price.

Younger men are far more likely to invest according to their values than their fathers were; 81% of millennial men in Morgan Stanley’s survey were interested in sustainable investing. And though fewer American men than women say they want to invest in companies with diverse leadership, the share is still sizeable, at 42%. If gender-lens investing is truly to take off, it will have to appeal to those who control the bulk of wealth—and that is still men.