Tech giants face new UK tax clampdown (BBC)

Some of the world’s largest technology firms are facing hefty new bills as the UK government moves to fundamentally change the way they are taxed.

Google and Facebook are braced for significant changes in the tax system after the Treasury told the BBC that a new tax on revenues was the “potentially preferred option”.

It would open up the firms’ huge UK sales numbers to the tax authorities.

At the moment, tax is levied on profits, a much smaller figure.

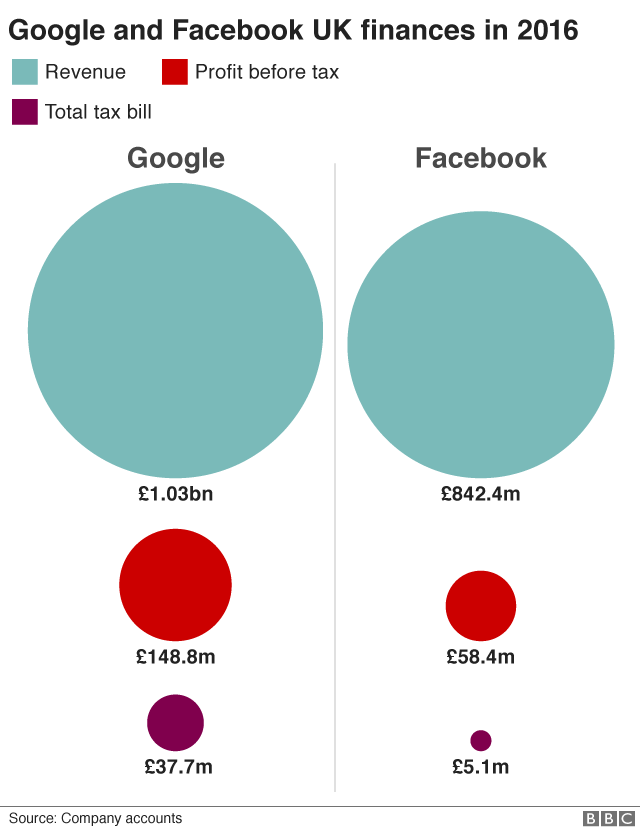

Google, for example, said it made sales – revenues – of £1bn in the UK in 2016 and a pre-tax profit of £149m.

It paid taxes of £38m – significantly higher than previous years after it changed the way it accounted for its activity in the UK.

If the government taxed a proportion of those sales its tax bill would be likely to increase significantly.

It would have a similar impact on a company like Facebook, which is also highly profitable and also increased the amount of tax it pays in the UK.

All the companies that have faced controversy have also made it clear that they abide by the present tax rules.

‘Fairly taxed’

The Financial Secretary to the Treasury told the BBC that large digital companies should pay a “fair” amount of tax.

“At the moment [they] are generating very significant value in the UK, typically through having a digital platform with lots of users interacting with that platform,” Mel Stride told me.

“That is driving a lot of value, so you’re looking at social media platforms, online marketplaces, internet search engines – where at the moment the tax regime is not taxing those activities fairly.

“We want to move to a situation where we are taxing those activities fairly.”

Technology companies have long argued that the tax rules are not their responsibility and that they follow the law.

Eileen Burbidge, of Tech City UK, said: “I don’t think the multi-national tech companies have been any different than any other commercially minded business, in that they’re certainly willing to pay their fair share or their responsible share of tax.”

Mr Stride said that a tax on revenues was the “potentially preferred route to go”, although he did not want to do anything that would harm smaller start-ups or companies that were still battling to make a profit.

In a consultation document on the issue, published alongside the Budget last year, the government did raise the prospect of a revenue tax.

That option now appears to have come a significant step closer.

“One important point to make right up front is we’re not talking about tax avoidance, evasion or non-compliance, we’re talking about the way the system works,” Mr Stride said.

“And we recognise that in the 21st century, the digital age, there’s a type of model of business where it’s actually difficult, using existing tax rules, to actually apply what most people would feel was a fair level of tax to those businesses.”

Mr Stride said that digital companies would pay higher levels of tax in a “number of cases” under the Treasury proposals.

He said the government wanted to work with partners in the European Union and at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development – which advises on global tax rules – to come to an international solution.

But if that proved too complicated, the government was prepared to “unilaterally enter into various changes”, he said.

Announcements about changes could come as early as the Spring Statement on March 13, the government’s major annual financial and economic policy statement, second only to the Budget.

Both France and Germany have said they want to see revenue taxes for digital firms after controversy over how much tax firms like Google, Facebook, Amazon and Apple pay.

The European Commission is also expected to come up with its own proposals next month.

But the OECD warned against “tax wars” breaking out if separate nations imposed different policies. That could also open up digital firms to being taxed multiple times across the globe on the same activity.

And could make the UK less attractive for digital firms like Google and Facebook – which employ thousands of people in Britain – to invest in.

‘Tax wars’

The OECD also questioned whether revenue taxes were the best way forward.

“Solving the challenges of the digitalisation of the economy clearly is a long-term issue, it’s going to take years,” Pascal Saint-Amans, the director of tax policy at the OECD, told the BBC.

“So what do you do? Is the stop gap measure – a tax on revenue – a good measure, probably not. Is it the best you can do given the political pressure you face in a number of countries, probably yes.

“But this needs to be in a frame to ensure that it’s not going to be the UK consumers who will have to pay for this tax.”

He said that China and America – which has recently changed its laws to oblige global firms to make large tax payments in the US – did not agree with “short term measures” and that global agreement was important.

“Unilateral measures may trigger some form of tax wars, and tax wars are no good for anyone,” Mr Saint-Amans said. “Thus the importance to have all countries – starting with the US, the Europeans, the Chinese and the others – to get together and to be serious in exploring solutions for the long-term.

“Without these we face the risk that all countries will be willing to protect the tax base and I think that’s a fair reaction that they may have.”

He added: “In the long-term, these companies – like all the others – should pay their taxes where they create value. And we need an agreement among countries of where is value created.

“Is the value of Google the algorithm, in which case it belongs to the US. Or is the value created by the consumption of the service, by the user contribution?”